Gimel

| Gimel | |

|---|---|

| Phoenician | 𐤂 |

| Hebrew | ג |

| Aramaic | 𐡂 |

| Syriac | ܓ |

| Arabic | ج |

| Phonemic representation | d͡ʒ, ʒ, ɡ, ɟ, ɣ |

| Position in alphabet | 3 |

| Numerical value | 3 |

| Alphabetic derivatives of the Phoenician | |

| Greek | Γ |

| Latin | C, G, Ȝ |

| Cyrillic | Г, Ґ, Ғ |

Gimel is the third (in alphabetical order; fifth in spelling order) letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician gīml 𐤂, Hebrew gīmel ג, Aramaic gāmal 𐡂, Syriac gāmal ܓ and Arabic ǧīm ج. Its sound value in the original Phoenician and in all derived alphabets, except Arabic, is a voiced velar plosive [ɡ]; in Modern Standard Arabic, it represents either a /d͡ʒ/ or /ʒ/ for most Arabic speakers except in Northern Egypt, the southern parts of Yemen and some parts of Oman where it is pronounced as the voiced velar plosive [ɡ] (see below).

In its Proto-Canaanite form, the letter may have been named after a weapon that was either a staff sling or a throwing stick (spear thrower), ultimately deriving from a Proto-Sinaitic glyph based on the hieroglyph below:

| |

The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek gamma (Γ), the Latin C, G, Ɣ and Ȝ, and the Cyrillic Г, Ґ, and Ғ.

Arabic ǧīm

[edit]| ǧīm | |

|---|---|

| ج | |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Arabic script |

| Type | Abjad |

| Language of origin | Arabic language |

| Sound values | /d͡ʒ/, /ʒ/, /g/, /ɟ/, /j/ |

| Alphabetical position | 5 |

| History | |

| Development | |

| Transliterations | ǧ, j |

| Other | |

| Writing direction | Right-to-left |

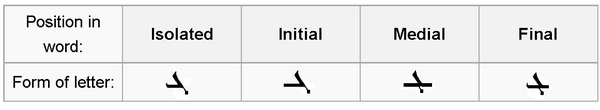

The Arabic letter ج is named جيم ǧīm / jīm [d͡ʒiːm, ʒiːm, ɡiːm, ɟiːm]. It has four forms, and is written in several ways depending on its position in the word:

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ج | ـج | ـجـ | جـ |

The similarity to ḥāʼ ح is likely a function of the original Syriac forms converging to a single symbol, requiring that one of them be distinguished as a dot; a similar process occurred to zāy and rāʾ.

Pronunciation

[edit]In all varieties of Arabic, cognate words will have consistent differences in pronunciation of the letter. The standard pronunciation taught outside the Arabic speaking world is an affricate [d͡ʒ], which was the agreed-upon pronunciation by the end of the nineteenth century to recite the Qur'an. It is pronounced as a fricative [ʒ] in most of Northern Africa and the Levant, and [ɡ] is the prestigious and most common pronunciation in Egypt, which is also found in Southern Arabian Peninsula. Differences in pronunciation occur because readers of Modern Standard Arabic pronounce words following their native dialects.

Egyptians always use the letter to represent [ɡ] as well as in names and loanwords,[1] such as جولف "golf". However, ج may be used in Egypt to transcribe /ʒ~d͡ʒ/ (normally pronounced [ʒ]) or if there is a need to distinguish them completely, then چ is used to represent /ʒ/, which is also a proposal for Mehri and Soqotri languages.

- The literary standard pronunciations

- [d͡ʒ]: In most of the Arabian Peninsula, parts of Algeria (Algiers dialect), Iraq, parts of Egypt, parts of the Levant. This is also the commonly taught pronunciation outside the Arabic speaking countries when Literary Arabic is taught as a foreign language. It is the agreed-upon pronunciation to recite the Qur'an and it also corresponds to ġ /d͡ʒ/ in Maltese (a Semitic language derived from Sicilian Arabic) as in ġar (neighbor) and Arabic جار (neighbor) both pronounced [d͡ʒaːr].

- [ʒ]: In the Levant (especially in the urban centers), Southern Iraqi Arabic, most of the Maghreb, and parts of Algeria (Oran dialect) and parts of western Saudi Arabia (Hejaz).[2]

- [g]: In Egypt, coastal Yemen (West and South), southwestern Oman, and eastern Oman.

- [ɟ]: In Sudan, parts of Saudi Arabia, and hinterland Yemen, as well as being a common reconstruction of the Classical Arabic pronunciation.

- Non-literary pronunciation

- [j]: In eastern Arabian Peninsula in the most colloquial speech, though sometimes [d͡ʒ] or [ʒ] in Literary Arabic loan words.

- [j]: In eastern Arabian Peninsula and Iraq but only colloquial speech, for example Kuwaiti Arabic وايد [waːjɪd] “a lot” vs. Najdi Arabic واجد [waːd͡ʒɪd].

- [ɟʝ]: attested among some bedouin dialects in Saudi Arabia.[3]

Historical pronunciation

[edit]While in most Semitic languages, e.g. Aramaic, Hebrew, Ge'ez, Old South Arabian the equivalent letter represents a [ɡ], Arabic is considered unique among them where the Jīm ⟨ج⟩ was palatalized to an affricate [d͡ʒ] or a fricative [ʒ] in most dialects from classical times. While there is variation in Modern Arabic varieties, most of them reflect this palatalized pronunciation except in coastal Yemeni and Omani dialects as well as in Egypt, where it is pronounced [g].

It is not well known when palatalization occurred or the probability of it being connected to the pronunciation of Qāf ⟨ق⟩ as a [ɡ], but in most of the Arabian peninsula (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, UAE and parts of Yemen and Oman), the ⟨ج⟩ represents a [d͡ʒ] and ⟨ق⟩ represents a [ɡ], except in coastal Yemen and southern Oman where ⟨ج⟩ represents a [ɡ] and ⟨ق⟩ represents a [q], which shows a strong correlation between the palatalization of ⟨ج⟩ to [d͡ʒ] and the pronunciation of the ⟨ق⟩ as a [ɡ] as shown in the table below:

| Languages - Dialects | Pronunciation of the letters | |

|---|---|---|

| ج | ق | |

| Proto-Semitic | [ɡ] | [kʼ] |

| Dialects in parts of Oman and Yemen1 | [q] | |

| Modern Standard Arabic2 | [d͡ʒ] | |

| Dialects in most of the Arabian Peninsula | [ɡ] | |

Notes:

- Western and southern Yemen: Taʽizzi, Adeni and Tihamiyya dialects (coastal Yemen), in addition to southwestern (Salalah region) and eastern Oman, including Muscat, the capital.

- As used in the Arabian Peninsula: in Sanaa; ق is [ɡ] in Sanʽani dialect and also in the literary standard (local MSA), whereas the literary standard pronunciation in Sudan is [ɢ] or [ɡ]. For the pronunciation of ج in Modern Standard Arabic, check Jīm.

Pronunciation across other languages

[edit]| Language | Alphabet name | Pronunciation (IPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Azeri | Arabic script | /d͡ʒ/ |

| Balochi | ||

| Brahui | ||

| Hindko | ||

| Javanese | Pegon | |

| Kashmiri | ||

| Kurdish | Sorani | |

| Malay | Jawi | |

| Pashto | ||

| Persian | ||

| Punjabi | Shahmukhi | |

| Saraiki | ||

| Sindhi | Arabic script | |

| Swahili | Ajami | |

| Urdu | ||

| Uyghur | ||

| Uzbek | Arabic script | |

| Hausa | Ajami | /d͡ʒ/ or /ʒ/ |

| Kazakh | Tote Jazu | |

Note: In Kazakh ⟨ج⟩ is pronounced /d͡ʒ/ in some dialects, such as in the south and east.[4]

Variant

[edit]A variant letter named che is used in Persian, with three dots below instead having just one dot below. However, it is not included on one of the 28 letters on the Arabic alphabet. It is thus written as:

| Position in word | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

چ | ـچ | ـچـ | چـ |

Hebrew gimel

[edit]Variations

[edit]| Orthographic variants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various print fonts | Cursive Hebrew |

Rashi script | ||

| Serif | Sans-serif | Monospaced | ||

| ג | ג | ג | ||

Hebrew spelling: גִּימֶל

Bertrand Russell posits that the letter's form is a conventionalized image of a camel.[5][6] The letter may be the shape of the walking animal's head, neck, and forelegs. Barry B. Powell, a specialist in the history of writing, states “It is hard to imagine how gimel = ‘camel’ can be derived from the picture of a camel (it may show his hump, or his head and neck!)”.[7]

Gimel is one of the six letters which can receive a dagesh qal. The two functions of dagesh are distinguished as either qal (light) or hazaq (strong). The six letters that can receive a dagesh qal are bet, gimel, daled, kaph, pe, and taf. Three of them (bet, kaph, and pe) have their sound value changed in modern Hebrew from the fricative to the plosive by adding a dagesh. The other three represent the same pronunciation in modern Hebrew, but have had alternate pronunciations at other times and places. They are essentially pronounced in the fricative as ג gh غ, dh ذ and th ث. In the Temani pronunciation, gimel represents /ɡ/, /ʒ/, or /d͡ʒ/ when with a dagesh, and /ɣ/ without a dagesh. In modern Hebrew, the combination ג׳ (gimel followed by a geresh) is used in loanwords and foreign names to denote [d͡ʒ].

Significance

[edit]In gematria, gimel represents the number three.

It is written like a vav with a yud as a "foot", and is traditionally believed to resemble a person in motion; symbolically, a rich man running after a poor man to give him charity. In the Hebrew alphabet gimel directly precedes dalet, which signifies a poor or lowly man, given its similarity to the Hebrew word dal (b. Shabbat, 104a).[8]

Gimel is also one of the seven letters which receive special crowns (called tagin) when written in a Sefer Torah. See shin, ayin, teth, nun, zayin, and tsadi.

The letter gimel is the electoral symbol for the United Torah Judaism party, and the party is often nicknamed Gimmel.[9][10]

In Modern Hebrew, the frequency of usage of gimel, out of all the letters, is 1.26%.

Syriac gamal/gomal

[edit]| Gamal/Gomal |

|---|

Madnḫaya Gamal Madnḫaya Gamal

|

Serṭo Gomal Serṭo Gomal

|

Esṭrangela Gamal Esṭrangela Gamal

|

In the Syriac alphabet, the third letter is ܓ — Gamal in eastern pronunciation, Gomal in western pronunciation (ܓܵܡܵܠ). It is one of six letters that represent two associated sounds (the others are Bet, Dalet, Kaph, Pe and Taw). When Gamal/Gomal has a hard pronunciation (qûššāyâ ) it represents [ɡ], like "goat". When Gamal/Gomal has a soft pronunciation (rûkkāḵâ ) it traditionally represents [ɣ] (ܓ݂ܵܡܵܠ), or Ghamal/Ghomal. The letter, renamed Jamal/Jomal, is written with a tilde/tie either below or within it to represent the borrowed phoneme [d͡ʒ] (ܓ̰ܡܵܠ), which is used in Garshuni and some Neo-Aramaic languages to write loan and foreign words from Arabic or Persian.

Other uses

[edit]Mathematics

[edit]The serif form of the Hebrew letter gimel is occasionally used for the gimel function in mathematics.

Character encodings

[edit]| Preview | ג | ج | گ | ܓ | ࠂ | ℷ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | HEBREW LETTER GIMEL | ARABIC LETTER JEEM | ARABIC LETTER GAF | SYRIAC LETTER GAMAL | SAMARITAN LETTER GAMAN | GIMEL SYMBOL | ||||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 1490 | U+05D2 | 1580 | U+062C | 1711 | U+06AF | 1811 | U+0713 | 2050 | U+0802 | 8503 | U+2137 |

| UTF-8 | 215 146 | D7 92 | 216 172 | D8 AC | 218 175 | DA AF | 220 147 | DC 93 | 224 160 130 | E0 A0 82 | 226 132 183 | E2 84 B7 |

| Numeric character reference | ג |

ג |

ج |

ج |

گ |

گ |

ܓ |

ܓ |

ࠂ |

ࠂ |

ℷ |

ℷ |

| Named character reference | ℷ | |||||||||||

| Preview | 𐎂 | 𐡂 | 𐤂 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | UGARITIC LETTER GAMLA | IMPERIAL ARAMAIC LETTER GIMEL | PHOENICIAN LETTER GAML | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 66434 | U+10382 | 67650 | U+10842 | 67842 | U+10902 |

| UTF-8 | 240 144 142 130 | F0 90 8E 82 | 240 144 161 130 | F0 90 A1 82 | 240 144 164 130 | F0 90 A4 82 |

| UTF-16 | 55296 57218 | D800 DF82 | 55298 56386 | D802 DC42 | 55298 56578 | D802 DD02 |

| Numeric character reference | 𐎂 |

𐎂 |

𐡂 |

𐡂 |

𐤂 |

𐤂 |

References

[edit]- ^ al Nassir, Abdulmunʿim Abdulamir (1985). Sibawayh the Phonologist (PDF) (in Arabic). University of New York. p. 80. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Mezzoudj, Fréha; Loukam, Mourad; Belkredim, Fatma. "Arabic Algerian Oranee Dialectal Language Modelling Oriented Topic". International Journal of Informatics and Applied Mathematics. Archived from the original on 21 April 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Il-Hazmy, Alayan (1975). A critical and comparative study of the spoken dialect of the Harb tribe in Saudi Arabia (PDF). p. 234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ Jankowski, H., Tazhibaeva, S., Özçelik, Ö., Abish, A., Aqtay, G., & Smagulova, J. (2023). "Kazakh". In L. Johanson (ed.), Encyclopedia of Turkic Languages and Linguistics Online. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/2667-3029_ETLO_COM_032116.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1972). A history of western philosophy (60th print. ed.). New York: Touchstone book. ISBN 0-671-31400-9.

- ^ Tenen, Stan. "Letter Portrait: Gimel". Meru Foundation. A Matrix of Meaning: Portraits of the Hebrew Letters, in Pictures and Words. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Powell, Barry B. (27 March 2009). Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization. Wiley Blackwell. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4051-6256-2.

- ^ Ginzburgh, Yitzchak; Trugman, Avraham Arieh; Wisnefsky, Moshe Yaakov (1991). The Alef-beit: Jewish Thought Revealed Through the Hebrew Letters. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 42, 389. ISBN 0-87668-518-1.

- ^ "Mass Rally for United Torah Judaism - Hamodia.com". Hamodia. 11 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Gedolim at Special Conference Call to Strengthen UTJ to Uphold Torah, Shabbos and Religious Character - Hamodia.com". Hamodia. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.