Javier Solana

Javier Solana | |

|---|---|

Solana in 1999 | |

| High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy | |

| In office 18 October 1999 – 1 December 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Jürgen Trumpf |

| Succeeded by | Cathy Ashton (Foreign Affairs and Security Policy) |

| Secretary General of the Council of the European Union | |

| In office 18 October 1999 – 1 December 2009 | |

| Preceded by | Jürgen Trumpf |

| Succeeded by | Pierre de Boissieu |

| Secretary General of the Western European Union | |

| In office 20 November 1999 – 1 December 2009 | |

| Preceded by | José Cutileiro |

| Succeeded by | Arnaud Jacomet |

| 9th Secretary General of NATO | |

| In office 5 December 1995 – 6 October 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Sergio Balanzino (Acting) Willy Claes |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Robertson of Port Ellen |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 16 June 1992 – 18 December 1995 | |

| Prime Minister | Felipe González |

| Preceded by | Francisco Fernández Ordóñez |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Westendorp |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francisco Javier Solana de Madariaga 14 July 1942 Madrid, Spain |

| Political party | Spanish Socialist Workers' Party |

| Spouse | María de la Concepción Giménez Díaz-Oyuelos |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Complutense University University of Virginia |

| Signature |  |

Francisco Javier Solana de Madariaga KCMG CYC (Spanish: [fɾanˈθisko xaˈβjeɾ soˈlana ðe maðaˈɾjaɣa]; born 14 July 1942) is a Spanish physicist and PSOE politician. After serving in the Spanish government as Foreign Affairs Minister under Felipe González (1992–1995) and as the Secretary General of NATO (1995–1999), leading the alliance during Operation Allied Force, he was appointed the European Union's High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy, Secretary General of the Council of the European Union and Secretary-General of the Western European Union and held these posts from October 1999 until December 2009.

Background and career as a physicist

[edit]Solana was born in Madrid, Spain. He comes from a prominent Spanish family, being a first cousin, twice removed, of diplomat, writer, historian, and pacifist Salvador de Madariaga[1] (Javier's grandfather, Rogelio de Madariaga and Salvador de Madariaga were cousins). His father was a chemistry professor, Luis Solana San Martín, who died when Javier was nineteen. His mother, Obdulia de Madariaga Pérez, died in 2005.[2][3][4][5][6] Javier is the third of five children.[2] His older brother Luis was once imprisoned for his political activities opposing the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, subsequently became a distinguished leader in the Spanish telecommunications industry[7] and was one of the first socialist members of the Trilateral Commission.[8]

Solana studied at the Nuestra Señora del Pilar School, an exclusive Catholic Marianist secondary school, before going to Complutense University (UCM). There as a student in 1963 he suffered sanctions imposed by the authorities for having organised an opposition forum at the so-called Week of University Renovation. In 1964 he clandestinely joined the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), which had been illegal under Franco since the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939. In the same year he graduated and then spent a year furthering his studies at Spain's Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and in the United Kingdom.

In 1965 he went to the United States, where he spent six years studying at various universities on a Fulbright Scholarship.[9] He visited the University of Chicago and the University of California, San Diego, and then enrolled in the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. There, he taught physics classes as a teaching assistant and carried on independent research; he also joined in the protests against the Vietnam War and was president of the Association of Foreign Students. He received his doctorate in physics from Virginia in 1971 with a thesis on Theory of the Elementary Excitation Spectrum of Superfluid Helium: the Roton Lifetime, extending his planned stay in the US by a year in order to continue his research. Returning to Spain he became a lecturer in solid-state physics at the Autonomous University of Madrid, UAM, and then in 1975 he became a professor at Complutense University. During these years he published more than 30 articles. For a time he worked as assistant to Nicolás Cabrera, whom he had met when Cabrera was professor at the University of Virginia. The last PhD dissertations that he directed were in the early 1990s.

Spanish politics

[edit]On returning to Spain in 1971 Solana joined the Democratic Co-ordination of Madrid as the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) representative.

In 1976, during PSOE's first national congress inside Spain since the civil war, he was elected Secretary of the party's Federal Executive Commission, and also Secretary for Information and Press, remaining in the post for five years. He was a close personal friend of the party's leader Felipe González, and is considered one of the PSOE leaders responsible for the transformation of the party in the post-Franco era. In 1976 he represented the PSOE at a Socialist International congress held in Suresnes, France, and again when it was held in Spain in 1977. On 20 May 1977 he accompanied González in visiting King Juan Carlos at the Zarzuela Palace.

He became a representative of a teachers' union in the Complutense University, and in this role won a parliamentary seat for PSOE on 15 June 1977 and represented Madrid region until December 1995. On 23 February 1981 he was in the parliament when it was taken over for 18 hours in an attempted coup by gunmen led by Antonio Tejero.

On 28 October 1982 PSOE won a historic victory with 202 out of 350 seats in the lower house. On 3 December, along with the other members of González's first cabinet, Solana was sworn in as Minister for Culture, where he remained until moving to the Ministry of Education in 1988. In July 1983 he adhered to the position of Alfonso Guerra calling for an exit of Spain from NATO.[10][11] On 5 July 1985 he was made the Spokesman for the Government for three years.

He was made Minister for Foreign Affairs on 22 July 1992, the day before the opening of the II Ibero-American conference of heads of state in Madrid, replacing the terminally ill Francisco Fernández Ordóñez. On 27–28 November 1995, while Spain held the Presidency of the Council of the EU, Solana convened and chaired the Barcelona Conference. A treaty was achieved between the twenty-seven nations in attendance with Solana gaining credit for what he called "a process to foster cultural and economic unity in the Mediterranean region".

It was during these thirteen years as a cabinet minister that Solana's reputation as a discreet and diplomatic politician grew. By going to the foreign Ministry in the later years of González administration he avoided the political scandals of corruption, and of the dirty war allegedly being fought against ETA, that characterised its last years. Towards the end of 1995, Solana – the only surviving member of González's original cabinet – was talked about in the press as a possible candidate to replace him and lead the PSOE in the following March elections. Instead, he made the leap to international politics.

During and after his spell as NATO secretary general (see below) Solana continued to play an active role in PSOE and Spanish politics. In June 1997, at the 34th PSOE Congress, Solana left their Executive Commission and joined their Federal Committee, being re-elected in second place three years later. By supporting Colin Powell's 5 February 2003 speech to the UN Security council which claimed that Iraq had WMD's[citation needed] Solana contradicted the position of his party leader José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, who opposed the PP government of José María Aznar's support for the invasion of Iraq. Solana is seen, along with González, as representing the older wing of the party. On 15 February 2005 he criticised the Plan Ibarretxe for its position on Basque Country independence, saying that its call for separate Basque representation within the EU had no place within the proposed EU constitution.

Secretary General of NATO

[edit]On 5 December 1995, Solana became the new Secretary-General of NATO, replacing Willy Claes who had been forced to resign in a corruption scandal. His appointment created controversy as, in the past, he had been an opponent of NATO. He had written a pamphlet called 50 Reasons to say no to NATO, and had been on a US subversives list.[citation needed] On 30 May 1982 Spain joined NATO. When PSOE came to power later that year, Solana and the party changed their previous anti-NATO positions into an atlanticist, pro-NATO stance. On 12 March 1986 Spain held a referendum on whether to remain in NATO, with the government and Solana successfully campaigning in favour. When criticised about his anti-NATO past, Solana argued that he was happy to be its representative as it had become disassociated from its Cold War origins.

Former Dutch Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers had been the leading candidate to replace Claes. According to the then-director of policy planning at the State Department, James Steinberg, Lubber's disagreement with the United States regarding NATO expansion caused concern in Washington: “we decided afterward that we weren’t going to let” Lubbers have the job.[12] The United States worked behind the scenes so as not to appear domineering in what is supposed to be an alliance-wide decision. In an attempt to play on French insecurities, Washington highlighted the French-language skills of Salona in comparison to Lubbers, who did not speak French. Sensing American opposition, Lubbers withdrew his candidacy in November 1995, and Solana became Secretary General in December of that year.

Solana immediately had to deal with the Balkans NATO mission Operation Joint Endeavour that consisted of a multinational peacekeeping Implementation Force (IFOR) of 60,000 soldiers which took over from a United Nations mission on 20 December. This came about through the Dayton Agreement, after NATO had bombed selected targets in Bosnia and Herzegovina (positions held by VRS) the previous August and September. He did this by deploying the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC). In December 1996 the ARRC was again activated, with IFOR being replaced by a 32,000-strong Stabilisation Force (SFOR) operating under codenames Joint Guard and later Joint Forge.

During Solana's term, NATO reorganised its political and military structure and changed its basic strategies. He gained the reputation of being a very successful, diplomatic Secretary General who was capable of negotiating between the differing NATO members and between NATO and non-NATO States. In December 1995 France partially returned to the military structure of NATO, while in November 1996 Spain joined it. On 27 May 1997, after five months of negotiations with Russian foreign minister Yevgeny Primakov, an agreement was reached resulting in the Paris NATO–Russia Founding Act.[13] On the same day, Solana presided over the establishment of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council to improve relations between European NATO and non-NATO countries.

Keeping the peace in the former Yugoslavia continued to be both difficult and controversial. IFOR and SFOR had received a lot of criticism for their inability to capture the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić. In late 1998 the conflict in Kosovo, between the Yugoslav authorities and the Kosovar Albanian guerilla Kosovo Liberation Army deteriorated, culminating in the Račak massacre on 15 January 1999, in which 45 Albanians were killed. NATO decided that the conflict could only be settled by introducing a proper military peacekeeping force under their auspices, to forcibly restrain the two sides.[citation needed] On 30 January 1999, NATO announced that it was prepared to launch air strikes against Yugoslav targets. On 6 February, Solana met both sides for negotiations at the Château de Rambouillet, but they were unsuccessful.

On 24 March, NATO forces launched air attacks on military and civilian targets in Yugoslavia. Solana justified the attacks on humanitarian grounds, and on the responsibility of NATO to keep peace in Europe and to prevent recurrences of ethnic cleansing and genocide similar to those which occurred during the Bosnian War (1992–1995).

Solana and NATO were criticised for the civilian casualties caused by the bombings.[14][15] On 23–24 April, the North Atlantic Council met in Washington D.C. where the Heads of State of the member nations agreed with the New Strategic Concept, which changed the basic defensive nature of the organisation and allowed for NATO intervention in a greater range of situations than before.

On 10 June, Serbian forces withdrew from Kosovo, and NATO stopped its attacks, which ended the Kosovo War. The same day UN Security Council Resolution 1244 authorised NATO to activate the ARRC, with the Kosovo Force launching Operation Joint Guardian and occupying the province on 12 June. Solana left NATO on 6 October 1999, two months ahead of schedule, and was replaced by George Robertson.

EU foreign policy chief

[edit]

After leaving NATO, Solana took up a role in the European Union. Earlier in the year, on 4 June 1999, he was appointed by the Cologne European Council as Secretary-General of the Council of the European Union. An administrative position but it was decided that the Secretary-General would also be appointed High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). In this role he represented the EU abroad where there was an agreed common policy. He took up the post on 18 October 1999, shortly after standing down from NATO. The post has a budget of €40 million, most of which goes to Balkan operations. From 25 November 1999 he was also appointed Secretary-General of Western European Union (WEU), overseeing the transfer of responsibilities from that organisation to the CFSP. In 2004 his 5-year mandate was renewed. He has also become president of the European Defence Agency.

The Clinton administration claimed in May 2000 that Solana was the fulfilment of Henry Kissinger's famous desire to have a phone number to talk to Europe.[citation needed] In December 2003 Solana released the European Security Strategy, which sets out the main priorities and identifies the main threats to the security of the EU, including terrorism. On 25 March 2004 Solana appointed Gijs de Vries as the anti-terrorist co-ordinator for the CFSP, and outlined his duties as being to streamline, organise and co-ordinate the EU's fight against terrorism.

On 29 June 2004 he was designated to become the EU's first "Union Minister for Foreign Affairs", a position created by the European Constitutional Treaty combining the head of the CFSP with that of the European Commissioner for External Relations. It would give a single voice to foreign policy and combine the powers and influence of the two posts with a larger budget, more staff and a coherent diplomatic corps. The position (colloquially known as "Mr. Europe") has been partly maintained in the Reform Treaty as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, but Solana is not going to take the post as he announced that he would step down at the end of his term.[16]

In late 2004, Solana held secret negotiations with Hamas leaders, saying that he met them at a time when there seemed to be an opportunity for progress, and were to "pass a clear message of what the international community wants", and said that the meetings occurred "months" before.[17]

Foreign affairs

[edit]

He negotiated numerous Treaties of Association between the European Union and various Middle Eastern and Latin American countries, including Bolivia and Colombia. Solana played a pivotal role in unifying the remainder of the former Yugoslavian federation. He proposed that Montenegro form a union with Serbia instead of having full independence, stating that this was done to avoid a domino effect from Kosovo and Vojvodina independence demands. Local media sarcastically named the new country "Solania".[citation needed]

On 21 January 2002 Solana said that the detainees at Guantanamo Bay should be treated as prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention.[18] The EU has stated that it hopes to avoid another war like the Iraqi invasion through this and future negotiations, and Solana has said the most difficult moments of his job were when the United Kingdom and France, the two permanent EU Security Council members, were in disagreement.

The so-called Vilnius letter, a declaration of support by eastern European countries for the United States' aim of régime change in Iraq, and the letter of the eight, a similar letter from the UK, Italy, and six second-tier countries, are generally seen [by whom?] as a low-water mark of the CFSP.

Solana has played an important role working toward a resolution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and continues to be a primary architect of the "Road Map for Peace," along with the UN, Russia, and the United States in the Quartet on the Middle East. On 22 July 2004 he met Ariel Sharon in Israel. Sharon had originally refused to meet Solana, but eventually accepted that, whether he liked it or not, the EU was involved in the Road Map. He criticised Israel for obstructing the Palestinian presidential election of 9 January 2005, but then met Sharon again on 13 January.

In November 2004 Solana assisted the United Kingdom, France and Germany in negotiating a nuclear material enrichment freeze with Iran. In the same month he was involved in mediating between the two presidential candidates in the post-election developments in Ukraine, and on 21 January 2005 he invited Ukraine's new President Viktor Yushchenko to discuss future EU membership.[19]

In 2010, after he had left office, Solana signed a petition along with 25 other EU leaders directed at his successor, Catherine Ashton, calling for EU sanctions on Israel in response to continued settlement construction in the West Bank.[20]

Other activities

[edit]- Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), Member of the Board of Trustees[21]

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Member of the Global Board of Advisors[22]

- Elcano Royal Institute for International and Strategic Studies, Member of the Board of Trustees[23]

- Global Leadership Foundation (GLF), Member[24]

- International Crisis Group (ICG), Board of Trustees (since 2010)[25]

- Munich Security Conference, Member of the Advisory Council[26]

- Project Syndicate, Contributor (since 2004)

- European Leadership Network (ELN), Senior Network Member[27]

Personal life

[edit]Solana is married to Concepción Giménez, and they have two adult children, Diego and Vega. He lives in Brussels, where his apartment has a reputation of being a focal point for Spanish politicians in or visiting this capital. Apart from his native Spanish, he also speaks fluent French, as well as English.

General Wesley Clark once asked Solana the secret of his diplomatic success. He answered: "Make no enemies, and never ask a question to which you do not know or like the answer."[19] He has been described as a "squarer of circles."[citation needed]

U.S. ambassador to NATO Alexander Vershbow said of him: "He is an extraordinary consensus-builder who works behind the scenes with leaders on both sides of the Atlantic to ensure that NATO is united when it counts."[citation needed] He is a frequent speaker at the prestigious U.S. based Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). He is likewise active in the Foreign Policy Association (FPA) as well as the New York City based East West Institute. In March 2010, Solana became honorary president of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, and in 2011 became a Member of the Global Leadership Foundation, an organization which works to promote good governance around the world. He also became a member of Human Rights Watch board of directors the same year.[28]

He is an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, a member of the Spanish section of the Club of Rome. He has received the Grand Cross of Isabel the Catholic in Spain and the Manfred Wörner Medal from the German defence ministry. He has been President of the Madariaga - College of Europe Foundation since 1998. He received the Vision for Europe Award in 2003. Also in 2003, he received the 'Statesman of the Year Award' from the EastWest Institute, a Transatlantic think tank that organizes an annual security conference in Brussels. In 2006 Solana received the Carnegie-Wateler peace prize. He has also been awarded the Charlemagne Prize for 2007 for his distinguished services on behalf of European unification.[29] In December 2009, Javier Solana joined ESADE Business School as president of its new Centre for Global Economy and Geopolitics. In January 2010, King Juan Carlos I appointed Javier Solana the 1,194th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece for his career in diplomacy.[30]

On 11 March 2020 Solana was admitted to the hospital after being infected by COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain.[31]

Awards and honours

[edit]Spanish honours

[edit] Knight Grand Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1996)[32]

Knight Grand Cross of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise (1996)[32] Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (1997)[33]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (1997)[33] Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (2000)[33]

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (2000)[33] Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (2010)[33]

Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (2010)[33]

Other countries

[edit] Grand Officer of the Order of the White Lion (Czech Republic, 1998)

Grand Officer of the Order of the White Lion (Czech Republic, 1998) Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (United Kingdom, 2000)[33]

Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (United Kingdom, 2000)[33]- Manfred Wörner Medal of the Federal German Ministry of Defence (Germany, 2002)[33]

Recipient of the Order for Exceptional Merits (Slovenia, 2004)

Recipient of the Order for Exceptional Merits (Slovenia, 2004) Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (Poland, 2005)[34]

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (Poland, 2005)[34] Commander Cross of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania, 2005)

Commander Cross of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania, 2005) Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic (Germany, 2007)[33]

Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic (Germany, 2007)[33] Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (Portugal, 2010)[35]

Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (Portugal, 2010)[35] Knight of the Georgian Order of the Golden Fleece (Georgia, 2010)[36]

Knight of the Georgian Order of the Golden Fleece (Georgia, 2010)[36]

Awards

[edit]- Vision for Europe Award, Edmond Israel Foundation (2003)[33]

- Statesman of the Year Award, EastWest Institute (2003)[33]

- Wateler Peace Prize, Carnegie Foundation (2006)[33]

- Peace Through Dialogue Medal, Munich Security Conference (2007)[33]

- Charlemagne Prize (2007)[33]

- Peace Award of the World Children's Parliament (2008)[33]

- Extraordinary Prize of the Spanish Ministry of Defence (2009)[33]

- Convivencia Award, Manuel Broseta Foundation (2009)[33]

- Charles V European Award, European Academy of Yuste Foundation (2010)[33]

- Ewald-von-Kleist Award, Munich Security Conference (2010)[33]/

- Knight of Freedom Award, the Casimir Pulaski Foundation[37]

- Honorary degree (political science), London School of Economics[33]

- Gold Medal of the Jean Monnet Foundation for Europe (2011)[33]

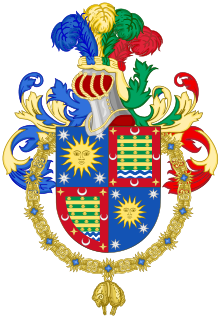

Arms

[edit]

|

|

See also

[edit]- Enlargement of the European Union

- Foreign Affairs Council

- History of Serbia and Montenegro

- History of the European Constitution

- History of the European Union

- List of European Union-related topics

- Politics of Europe

References

[edit]- ^ Biography of Luis Solana (brother of Javier Solana) at his blog Archived 12 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Spanish):

Heredó de su abuelo materno [Rogelio de Madariaga y Castro] la revista "España Económica", publicación que dio cabida a jóvenes economistas críticos con el régimen de Franco. Sobrino nieto de D. Salvador de Madariaga.

He inherited from his maternal grandfather [Rogelio de Madariaga y Castro] the magazine "España Económica", which accommodated young economists critical of the Franco regime. (He's) the grand nephew of D. Salvador de Madariaga - ^ a b "ABC (Madrid) - 17/04/2005, p. 86 - ABC.es Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.abc.es. 3 September 2019.

- ^ Movimiento nobiliario 1934 Archived 25 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, page 167. News about the marriage between Luis Solana San Martín and Obdulia Madariaga.

- ^ ¡Feliz Navidad, Maribel!, post in Luis Solana's blog (Luis Solana is Javier's brother) and the post accounts mentions the five brothers.

- ^ Death notice of Enrique de Madariaga y Pérez-Gros. It mentions Obdulia as sister and Luis Solana San Martín as brother-in-law.

- ^ Death notice of Juana San Martín Yoldi, widow of Ezequiel Solana. It mentions all her sibling, including Luis.

- ^ "Biografia". Luis Solana. Archived from the original on 12 June 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "Trilateral Commission Annual Meeting Publications". Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "CIDOB". Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ Roldán, Juan (20 July 1983). "Los ministros Solana, Maravall, Lluch y Campo coinciden con Guerra en que España no debe permanecer en la OTAN". El País.

- ^ Ordás, Carlos Ángel (2014). "OTAN de entrada No. El PSOE y el uso político de la integración española en el Pacto Atlántico o cómo hacer de la necesidad virtud, 1980-1986" (PDF). In Carlos Navajas Zubeldía & Diego Iturriaga Barco (Coords.) (ed.). España en democracia: Actas del IV Congreso de Historia de Nuestro Tiempo. p. 298. ISBN 978-84-617-1203-8.

- ^ Not One Inch, M.E. Sarotte, p 278-238

- ^ "NATO - Official text: Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed in Paris, France, 27-May.-1997". NATO.

- ^ "New Figures on Civilian Deaths in Kosovo War(Human Rights Watch Press Release, Feb. 7, 2000)". Hrw.org.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch Letter to NATO Secretary General Concerning Allaged Violations of the Laws of War. (13 May 1999)". Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Middle East - EU denies secret talks with Hamas". Bbc.co.uk. 25 November 2004.

- ^ "Solana urges POW status for Afghan captives". The Irish Times. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ a b Clark, Wesley K. Waging Modern War. New York: Perseus Books Group, 2001–2002, p. 15

- ^ "Former EU leaders urge sanctions for Israel settlements". BBC News. 10 December 2010.

- ^ Governance Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal).

- ^ Global Board of Advisors Council on Foreign Relations (CFR).

- ^ Board of Trustees Elcano Royal Institute for International and Strategic Studies.

- ^ Membership Archived 6 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine Global Leadership Foundation (GLF).

- ^ Crisis Group Announces New Board Members International Crisis Group (ICG), press release of 1 July 2010.

- ^ Advisory Council Munich Security Conference

- ^ "Senior Network". Europeanleadershipnetwork.org. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Solana, Jilani, and Matsumoto Join Human Rights Watch Board". Human Rights Watch. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen – News". Archived from the original on 5 January 2007.

- ^ "OTRAS DISPOSICIONES : JEFATURA DEL ESTADO" (PDF). Boe.es. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Former NATO chief Javier Solana has coronavirus - source". Reuters. 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Javier Solana's Order of Alfonso X, the Wise appointment. Spanish Official Journal (96/01/27) (PDF)" (PDF). Boe.es. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r (in Spanish)Javier Solana Madariaga, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs Archived 5 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Pujol glosa la defensa identitaria al recibir la cruz del mérito de Polonia". El País. 10 November 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Javier Solana knight of the Christ Order, Que.es". Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Saakashvili condecora a Solana por su apoyo a los intereses de Georgia". que.es. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ "Javier Solana". Pulaski.pl. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Ceballos-Escalera Gila, Alfonso de, Marqués de la Floresta; Mayoralgo y Lodo, José Miguel de, Conde de los Acevedos (1950-); Menéndez Pidal, Faustino (1996). La Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro y su armorial ecuestre. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional and Ed. Toisón ISBN 978-84-922198-0-3

- ^ "S O L A N A". 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "M A D A R I A G A". 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

External links

[edit]- Javier Solana at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) (in Spanish) (updated to 2010[update])

- Solana steps down as EU foreign policy chief

- EU's quiet diplomat steps aside after 10 years

- Curriculum Vitae of Javier Solana

- Assessment of next NATO Secretary General Archived 6 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Civil liberties and Solana

- Euro-Mediterranean Partnership for Peace

- European Neighbourhood Policy

- NATO Declassified - Javier Solana (biography)

- Javier Solana at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Interview about EDSP Archived 16 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Interview as Spanish foreign minister in conflict with Canada

- Interview with Physics world magazine

- Online Resource Guide to EU Foreign Policy

- Madariaga European Foundation

- Shorter biography of Javier Solana

- Solana's development of a Common Foreign and Security Policy

- Solana meets Sharon, July 2004

- The puzzle of Solana's power

- Book about Javier Solana, 2011

- 1942 births

- Commander's Crosses of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Academic staff of ESADE

- Foreign ministers of Spain

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Christ (Portugal)

- Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Grand Officers of the Order of the White Lion

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Living people

- Members of the constituent Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the 1st Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the 2nd Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the 3rd Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the 4th Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Members of the 5th Congress of Deputies (Spain)

- Politicians from Madrid

- Political office-holders of the European Union

- Recipients of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise

- Recipients of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland

- Recipients of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Georgia)

- Secretaries general of NATO

- 20th-century Spanish physicists

- Spanish Socialist Workers' Party politicians

- University of Virginia alumni

- Western European Union people

- Culture ministers of Spain

- Spanish officials of the European Union

- Center on International Cooperation

- Human Rights Watch people

- Recipients of the Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 3rd class

- 20th-century Spanish politicians

- 21st-century Spanish politicians

- 20th-century Spanish diplomats

- 21st-century Spanish diplomats

- Secretaries-general of the Council of the European Union